Here’s my idea of a good math lesson. I want to explain Euler’s formula, the cornerstone of multidimensional mathematics, and one of the truly beautiful ideas from history. In school this formula appears as a useful trick, and is not commonly understood. I think that is because students are denied enough time to wonder what the formula actually means (it doesn’t describe how to pass an exam). Here is Euler’s formula:

This idea was introduced to me after a review of imaginary and complex numbers. Once the history and definition were out of the way, we completely freaked out at the idea of putting ‘i’ in the exponent, then practiced how to use it in calculations. I might have had a brief moment of clarity in that first class, but by the AP exam Euler’s formula was nothing more than a black box for converting rectangular coordinates to polar coordinates.

Many years later, I came across the introduction to complex numbers from Feynman’s Lectures on Physics, and suddenly the whole concept clicked in a way that it never had in school. Explained here, I don’t think it is really that difficult to understand, but then I’ve already managed to understand it, so I’ll try to communicate my understanding and then you can tell me whether it makes sense.

We need to start by generalizing the concept of a numeric parameter. The number line from grade school is an obvious way to represent a system with one numeric parameter. If we label the integers along this line, each mark corresponds to a grouping of whole, countable things, and the value of our integer parameter must refer to one of these marks. If we imagine a similar system where our parameter can “slide” continuously from one integer to the next, the values that we can represent are now uncountable (start counting the numbers between 0.001 and 0.002 if you don’t believe me) but opening up this unlimited number of in-between values allows us to model continuous systems that are much harder to represent with chunks.

Each system has a single numeric parameter, even though the continuous floating-point parameter can represent numbers that the integer parameter cannot. In physics, the continuous parameter can represent what is called a “degree of freedom,” basically a quantity that changes independently of every other quantity describing the system. Sometimes a “degree of freedom” is just like one of the three dimensions that you can see right… now, but this is not always the case. Wavefunctions in particle physics can have infinite degrees of freedom, even though the objects described by these esoteric equations follow different laws when we limit our models to the four parameters of spacetime.

Anyway, the imaginary unit or ‘i’ is just some different unit that identifies a second numeric parameter. If we multiply an integer by ‘i’, we’re basically moving a second parameter along its own number line that same distance. Apply the “sliding” logic from before and we can use the fractional parts between each imaginary interval. If this sounds new and confusing, just remember that any “real” number is itself multiplied by the real unit, 1. Personally, I don’t think that the word “imaginary” should be used to describe any kind of number, because all numbers are obviously imaginary. However, this convention exists regardless of how I feel about it, and nobody would know what to put in Google if I used a different word.

Why do teachers use this system where one implicit unit is supplemented by a second explicit unit? Simple – it was added long before anyone fully understood what was going on. The imaginary unit was the invented answer to a question, that question being:

Which number yields -1 when multiplied by itself?

The first people to ask this question didn’t get much further than “A number called ‘i’ which is nowhere on the number line, and therefore imaginary.” If those scholars had described their problem and its solution in a different way, they might have realized some important things. First, this question starts with the multiplicative identity (1) and really asks “which number can we multiply 1 by twice, leaving -1?” Thinking about it like this, it soon becomes clear that the range of values we can leave behind after multiplying 1 by another value on the same number line, twice, cannot include -1! We can make 1 bigger, twice, by multiplying it by a larger integer, or smaller, by multiplying it by a value between 0 and 1. We can also negate 1 twice while scaling it up or down, but none of these options allow for a negative result!

A clever student might point out that this is a stupid answer and that we might as well say there is none, but we still learn about it because amazing things happen if we assume that some kind of ‘i’ exists. We can imagine a horizontal number line, and then a second number line going straight up at 90° (τ/4 radians, a quarter turn) from the first. Moving a point along one line won’t affect its value on the other line, so we can say that the value of our ‘i’ parameter is represented on the vertical line and the value of our first (“real”) parameter is represented on the horizontal line. That is, a complex number (a*1+b*i) imagined as a single point on a 2-dimensional plane. In this space, purely “real” or purely “imaginary” numbers behave just like complex numbers with zero for the value of one parameter.

Now think about the answer to that question again. If our candidate is ‘i’ or some value up “above” the real number line, it’s easy to imagine a vector transformation (which we assume still works like multiplication) that can change 1 to ‘i’ and then ‘i’ to -1 in this 2D number space. Just rotate the point around the origin by 90°. When our parameters are independent like this, exponentiation by some number of ‘i’ units is exactly like rotating the imagined “point” a quarter turn around zero some number of times. I don’t really know why it works, but it works perfectly!

We’ve seen that imaginary units simply measure a second parameter, and how this intuitively meshes with plane geometry. Now let’s review what is actually going on. Numbers multiplied by ‘i’ behave almost exactly like numbers multiplied by 1, but the important thing about all ‘i’ numbers is that they are different from all non-‘i’ numbers and therefore can’t be meaningfully added into them. The ‘i’ parameter is a free parameter in the two-parameter system that is every complex number. It can get bigger or smaller without affecting the other parameter.

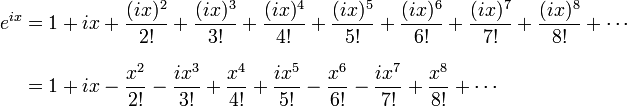

Bringing this all together, let’s try to understand what Euler was thinking when he wrote down his formula, and why it was such a smashing success. He noticed that the Taylor series definition of the exponential function:

Becomes this:

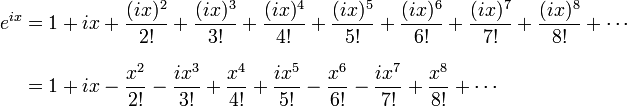

When ‘i*x’ is the exponent, because the integer powers of ‘i’ go round our complex circle from 1 to i to -1 to -i and back. Grouping the real terms and the ‘i’ terms together suddenly and unexpectedly reveals perfect Taylor series expansions of the cosine and sine:

As each expansion is multiplied by a different free parameter, the two expansions don’t add together, naturally separating the right side of our equation into circular functions! We can just conclude that those functions really are the cosine and sine of our variable, remembering that the sine is an ‘i’ parameter, and it works! Because these expressions are equivalent, having a variable in the exponent allows us to multiply our real base by ‘i’ any fractional number of times (review your exponentials), and thus rotate to any point in the imagined complex plane. There are other ways to prove this formula, but I still do not understand exactly why any of the proofs happen the way they do. It’s not really a problem, because Euler probably didn’t understand it either, but I’d still like to come across a good answer someday. What I know right now is that any complex number can be encoded as a real number rotated around zero by an imaginary exponent:

Here is proof that certain systems of two variables can be represented by other systems of one complex variable in a different form, and the math still works! Euler’s formula is a monumental, paradigm-shattering shortcut, and it made the modern world possible. I’m not overstating that point at all, everything from your TV to the Mars rover takes advantage of this trick.